Gun Review: Springfield Armory M1A

The M14 was the last U.S. standard issue, select-fire infantry rifle chambered for a full-power .30 caliber class cartridge.

Less than ten years after Uncle Sam issued the M14 to the troops, the M16 succeeded the “United States Rifle, 7.62 mm, M14." And yet the M14 remains in service, for three reasons: durability, reliability and accuracy. Springfield Armory’s semi-automatic M1A is all that and a bag of chips and you don’t have to enlist to get our hands on one . . .

With its walnut stock and Parkerized metal, the Springfield M1A is a line-by-line clone of the as-issued M14, from its flash hider (or a muzzle break in AWB states) to its butt flapper. While the M1A is a semiautomatic-only rifle it’s close enough to the fully-automatic M14 to make the most grizzled Vietnam vet turn all dewy-eyed.

The Quest for (Select) Fire -- and Back

Popular culture has decided that a submachine gun is any automatic rife. In fact, the term refers to a fully-automatic rifle that fires pistol-caliber cartridges. Throughout much of WW2, U.S. infantrymen used submachine guns to great effect. While soldiers could lay down a curtain of fire the guns proved to be underpowered (i.e., not lethal enough) in many circumstances.

The Browning BAR---designated “Rifle, Caliber .30, Automatic, Browning, M1918"---had plenty of power. It fulfilled the Army's need for effective, full-power “walking fire.” Shot from a tripod or lightweight bipod, the M1918 (and subsequent variants) were effective light machine guns. When fired from the shoulder or hip, not so much.

What the War Department really wanted (and the boys in OD or khaki really needed):

Was a lighter full-auto firearm that was handier that the BAR and yet more powerful than a submachine gun. The perfect replacement rifle would also have a manual of arms close to the M1 Garand so troops and armorers would need minimal retraining. In other words, our fighting forces needed a select fire M1 Garand.

The War Department turned to Springfield Armory and its top designer, John C. Garand, to create the new battle rifle. Designated T20E2, the rifle was developed by Springfield Armory and ordered into production in mid-1945. Hearing about the U.S. Army’s plan to equip a bazillion infantrymen with a select fire battle rifle, encouraged by two atomic bombs, the Japanese Emperor surrendered immediately.

As soon as the guys with the rising sun flag ran up a white one, the War Department cancelled the order for the T20E2 and abandoned the field. A Belgian arms manufacturer filled it with a rifle it called the Fusil Automatique Léger. We know that rifle today as the brilliant FN FAL. The world came to know it as The Right Arm of the Free World.

The Right Arm of the Free World could have been the M14.

It should have been the M14. But there was no M14. It hadn’t really been shelved so much as back-burnered.

The American arms manufacturers had been dealt a setback, but there wasn't a lot of quit in them. Development of the select fire Garand slowed, but didn't cease during the late ‘40s and early ‘50s. After many fits and starts, SA devised the T44 series, which was to morph into the M14. Eventually.

While the Ordnance Department was resting on its laurels (that's the fleshy part of the human anatomy just below the tailbone), FN was forging ahead.

Guessing that adoption by the US would lead to a host of NATO contracts, FN wisely granted the US government the right to produce an Americanized version of the FAL domestically at the grand cost of exactly zip. Zilch. Zero. Nada. Which was actually less than what the DoD wanted to spend.

The Army held shoot-offs between Springfield Armory’s T44E4 and the T48 (the designation for the American FAL) in 1955 and 1956. And the winner was . . . nobody. The final test was deemed a tie. A year later, the US decided in favor of – surprise! -- the T44E4 as the standard US service rifle M14.

With the aid of a calculator, I was able to determine that ten years had passed since the War Department had canceled its order for the T20E2, and $100m had been spent on the military’s bumbling quest for select fire. And yet, not a single rifle had been issued to the troops who needed them.

When the production M14s were finally issued, they weren’t all that wonderful.

There were, uh, glitches. Most were fixed. By the time that the M14 was issued in significant numbers, the year was 1962 and the Cold War was getting warm in places like Cuba and Vietnam.

Initial Marine units dispatched to Vietnam in 1965 were carrying M14s.

While the soldiers and Marines loved their M14s, the rifle---like its FN FAL competitor---was overwhelmed in full auto mode by the power of the 7.62 NATO round. Uncle Sam issued many with their selectors pinned. In semi-auto mode, the rifle was deadly accurate and punched through the jungle flora with ease.

Still, such a big rifle was unhappy in tight spaces.

Thanks to the hot wet climate of Southeast Asia, the Army had to replace the M14's wood stocks with composite. The additional cost factored into the Army's decision to phase-out the M14, starting in 1966. It was replaced by a little black rifle that many of the troops believed was made by Mattel and many soldiers and Marines just plain despised.

Springfield Armory Inc. (unrelated to the Springfield Armory that closed in 1968) began to produce the semi-auto M1A around 1974 using surplus GI M14 parts. The M1A launched SA, Inc. as a top shelf firearms manufacturer. The rifle has been popular ever since.

First Impressions

From the moment I removed the tester from its factory box, I knew that I was holding a real rifle. I’ve had the same visceral reaction to battle rifles from World War II, also crafted from actual wood and blued or Parkerized metal. What all those rifles have in common is real firepower and real weight. The M1A has both of those in spades.

Based as it is on its military daddy, the M1A is built like the proverbial brick outhouse. The rifle's wood is solid, denser than the fluffiest Playboy bunny. The metal is beefier than a Triple Meat Whataburger. Every component seems like it was made from 2” frontal armor salvaged from a decommissioned tank.

The M1A Standard could be made lighter by shaving metal here and there or using composite materials like the SOCOM II variant. But then it wouldn’t feel like an old-school battle rifle. Shake a typical AR and it sounds like something a baby might enjoy teething on. Shake the M1A and you’ll hear nothing except your tendons popping.

The M1A is also a big rifle.

While not as long as, say, a Mosin Nagant, the M1A is over 44 inches in length. It will never be confused with a jungle carbine. While the M1A is no more designed for urban warfare than Donna Feldman, in open country the rifle's 22” barrel creates a long sight radius, promising accuracy well beyond the 300-yard “theoretical” accuracy limit of the carbine-length M16.

The first M14 prototypes had wooden hand guards. WHich caught fire during rapid fire endurance testing. As the M14 wasn’t spec’d by the military as a secondary source of kindling for the troops, the Army replaced the wood by vented plastic. Alas, those plastic guards proved too flimsy for combat use, so they were in turn replaced by solid, ridged plastic hand guards like . . . the one on Springfield’s M1A.

The M1A is as muzzle heavy as an Irish Setter.

A full ten round magazine moves the balance point slightly aft. With a loaded twenty round mag the M1A would probably be better balanced than Nik Wallenda. I couldn't test my hypothesis; the Commonwealth of Massachusetts discourages the possession of large(r) capacity magazines through the imposition of custodial sentences.

The M1A’s front sight is a straightforward military blade with protective ears. The rear sight is adjustable for windage and elevation, but there’s only one aperture. The peep sight---barely 1/16th” in diameter---looks to be useless at close range but effective at distance.

Yanking and releasing the M1A’s operating rod handle required no more force than charging my old man’s 1959 Johnson Sea Horse 10 HP outboard. Unlike dad’s old blender, the M1A starts on the first pull. Releasing the handle produces a sound that reminds me of a bear trap slamming shut, only without the bear. It’s loud, authoritative and intimidating. In fact, the rack of a twelve gauge pump sounds like a jingle bell compared to the metallic percussion of the M1A’s rotating bolt as it slams home.

Yanking and releasing the M1A’s operating rod handle required no more force than charging my old man’s 1959 Johnson Sea Horse 10 HP outboard. Unlike dad’s old blender, the M1A starts on the first pull. Releasing the handle produces a sound that reminds me of a bear trap slamming shut, only without the bear. It’s loud, authoritative and intimidating. In fact, the rack of a twelve gauge pump sounds like a jingle bell compared to the metallic percussion of the M1A’s rotating bolt as it slams home.

OK, it’s built like a tank, or maybe from a tank. But how does it shoot?

The Yin

Due to some seriously crappy New England weather, I first shot the M1A at 25 yards, indoors. Short distance shooting isn’t much of a test for an old school battle rifle, but it gave me an opportunity to get familiar with the controls. While loading and firing M1A is mostly intuitive, deactivating the safety by placing your finger inside the trigger guard is about as unintuitive as it gets.

I was shooting offhand, since I had little desire to prone myself out or sit my booty down on a range floor covered with enough lead dust to block nuclear fallout. In this stance, the sling's the thing. Someone ought to tell Springfield to include one with the rifle. [ED: mission accomplished.]

As expected, the M1A's little peep sight was a problem. Between the tiny aperture and the rugged front blade (with its bat-shaped ears) most of the target was obscured at 25 yards. Keeping the barrel-heavy rifle's muzzle steady and the sights on target was a challenge. Zeroing the M1A was, as they say, "a process."

I enjoyed every minute of it.

The flapper, designed to help retain the cleaning stuff stored in the buttstock, damped the recoil of the 7.62X51 cartridges. This rifle that dishes out the punishment on the muzzle end only.

Once the weather broke, I was able to tote the rifle out to the West Barnstable Town Range, where I fired off about six boxes of 7.62 NATO happiness before the sky opened up and another dose of Massachusetts Liquid Sunshine closed out my session. As expected, the rifle proved to be very accurate. But that’s the least interesting part of the story.

Return to Ia Drang

Before I even had a chance to load, I noticed someone nearby who looked ready to take a trip down memory lane. My cohort was peppering a target at fifty yards with his Ruger M1911, shooting from a sandbag rest. While I was busy uncasing the M1A on the hundred yard line, the pistol shooter saw the rifle and I saw that he saw. I knew that look. I motioned for him over.

I recognized his walk.

I’d seen it before on a hundred guys who'd spent their time in the rice paddies and forests over there and in the woods over here. It was a walk that wouldn’t snap a twig or trip a hidden wire.

"Bob" fired off a few very accurate shots and smiled. “It’s like meeting an old friend." He carried an M14 back in the day, before the military transitioned to the M16. He loved his M14, claiming it was a thousand yard gun. While I don’t believe that anyone should actually love an inanimate object, I guess it’s alright when the object saves your life.

Bob’s son, who’d been shooting a heavy-barreled 10/22 Target Model to good effect, took a few shots with the M1A. So did the son’s friend who’d been plinking away with a Marlin .22. The father said, “It’s a man’s gun.” We all nodded. Bob went back to his spot on the fifty yard line smiling. When he left 45 minutes later, he still was. So was I.

The Yang

The M1A was born to shoot at distance.

The further away the target, the better the small peep sight works. Of course, if offhand shooting is tough at 25 yards, it’s really tough at 100 or more. So, I brought out my handy little WinMart sandbags for a bit of nonverbal support.

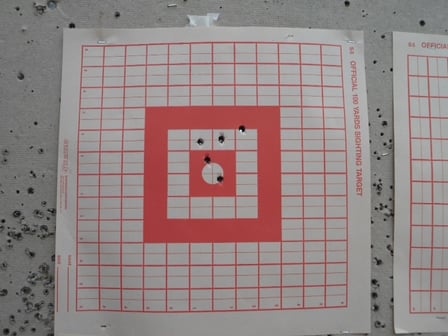

I’d zeroed it at 25 yards, so I was a little high with my first three slow-fire shots at 100. I’d forgotten to bring a spotting scope, so I had no idea if I was even on paper until I took the walk downrange. Once I realized that my shots were pretty well centered but up there, I made the necessary corrections. Thereafter, I had no trouble depositing the next two shots centered and less than an inch apart.

It soon became apparent that if I kept up the protocol of walking out to my target to check my shots every time, I'd shortly trample out my own personal game trail and piss off the other shooters at the line at the same time. I needed instant feedback, so I lined up about 20 discarded shot shells that I found scattered about. The M1A proved to be a shot shell killer supreme, launching one after another into near earth orbit with ease at the slightest provocation.

Rapid fire accuracy at 100 yards proved to be very good as well.

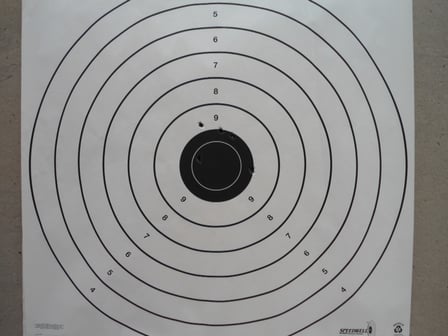

This group of five shots – four in the black -- was fired as quickly as I could manage to acquire the target and pull the trigger. The rifle isn’t punishing to shoot and there’s no muzzle blast. But muzzle rise is pronounced and it does take a microsecond or two to get the gun back on target. Here’s a viddy of our friend and TTAG commenter Greg from Allston shooting the M1A, from a tripod rest. You can see the obvious hop.

Warts and all (and there are damn few warts), I enjoyed this rifle more than anything else that I’ve shot in many years. While its accuracy is excellent and the build quality very robust, what I liked most about it was the sense of holding history in my hands. What I liked least: I’d have to send this rifle back to SA when the testing was through. Fortunately, that’s a correctable situation.

Conclusion

The odds of me having to tote a rifle in battle are about the same as snagging a long weekend on the French Riviera with Salma Hayek. But if I did -- go into battle, that is -- I’d feel secure with an M1A. In the Commonwealth we can’t use rifles to shoot Bambi. The only feral pigs around here are in the General Assembly. But if I could hunt with the M1A, I would.

As a vicious and enthusiastic destroyer of paper and other targets, I’m confident blazing away with the M1A at distances further than I can see. In fact, there’s not much that I want to do with a rifle that I can’t do with Springfield Armory’s classic M1A.

SPECIFICATIONS

Model: Springfield Armory Model MA9102 Standard M1A

Caliber: 7.62 X 51 NATO

Magazine capacity: 10 rounds

Materials: Parkerized barrel and magazine, walnut stock

Weight empty: 9.3 pounds

Barrel Length: 22″

Overall length: 44.33″

Sights: Blade front, adjustable aperture rear

Action: Semi-automatic, gas operated, piston driven

Price: MSRP $1739 ($1409 at Bud’s Gun Shop when in stock)

RATINGS (out of five stars)

Style * * * * *

75 year old styling never looked so modern. If you like the looks of the M1 Garand, you’ll love the looks of the M1A. It’s sleeker than the pot-bellied Garand and the muzzle device of your choice really dresses it up. The wood has a bit of figure, too. It’s not AAA Grade Fancy, but it’s still decent stuff.

Accuracy * * * * *

I never shot much better than 1.25" groups with the iron sights and basic milspec ammo. I did not fire this rifle with optics, but I expect that it would shoot 1 MOA or better out of the box with a good scope and good target ammo.

Ergonomics * * * *

Compared to the M16 that replaced the M14, the M1A is too heavy and too long. Compared to the M1 Garand that was replaced by the M14, the rifle is lighter by about two pounds and far, far easier to load because of its external magazine. It comes to shoulder naturally and seems to become part of the shooter’s body.

Ergonomics (firing) * * * * *

The safety works as it’s supposed to, but I didn't enjoy having to put my finger inside the trigger guard to deactivate it. The cheek weld is great, and aligning the sights is virtually automatic. Shooters who prefer a single stage trigger will be disappointed in the box-stock trigger. Those who prefer a two-stage military style trigger will love this one as much as I did. It’s totally free of creep and breaks cleanly at around 5 pounds after 3/16th inch of feathery takeup. There’s muzzle rise to be sure, but recoil is well damped. The short LOP worked fine for me, but shooters with the wingspan of a California condor will need a butt pad. For the rifle, that is.

Reliability * * * * *

A half dozen shooters pumped two hundred rounds of Federal XM80C through the M1A in three range sessions, firing the gun dirty, with zero issues. Despite the archaic feed system, there were no misfeeds, no stoppages, nothing bad at all. Sometimes archaic is good. I can’t imagine this rifle ever letting me down.

Customize This * * *

It’s more customizable than one would think. The flash hider can be swapped out for a muzzle brake and there’s scope mounts available from a few manufacturers. Variants of the M1A are offered by SA including “tactical” models, and there are many aftermarket goo-gahs, stocks and unnecessary accoutrements awaiting purchase by those with more money than taste. But please, shooters, if you buy a Standard model, just keep it standard. Okay?

OVERALL RATING * * * * *

It’s a truly classic rifle. The only way it could be any better would be to restore that functional selector switch.