As a long-time firearms instructor and head of a gun rights group, people ask me all sorts of questions. All questions have merit, especially for people new to guns. Among these questions, folks will ask about the safety of shooting old ammunition.

I tell them that in general, old factory-loaded ammunition should be safe to shoot.

The ammo gods showered me with old ammo these past few days.

A long-time friend and fellow instructor cleaned out his garage and found several hundred rounds of old .22 Blazer ammo.

Yeah, it looks rough. At the same time, I’ve shot plenty of old .22s and they usually function pretty well. I would not use them for a match or competition, but for plinking or skills-building? You bet.

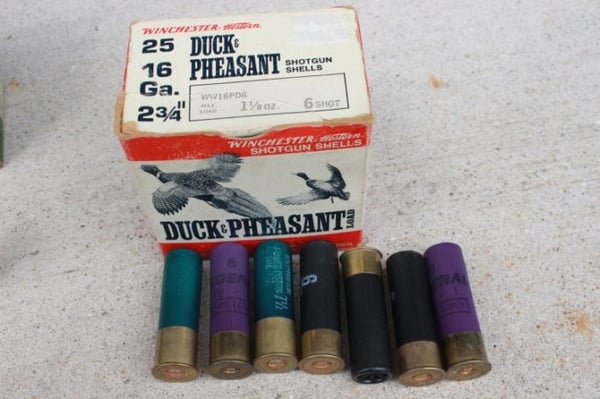

Another friend came upon a massive collection of old shotgun shells at a sale.

More than he could use. So he shared the wealth. In fact, he shared boxes and boxes of shotshell wealth, about a hundred pounds’ worth.

I cheerfully accepted the windfall, as I know shotgun ammunition also does well, regardless of age. Unless one stores shotgun shells at the bottom of Lake Michigan after a boating accident, shotgun ammo tends to forgive owners who store them under less-than-ideal conditions.

If you have old shotshells that do not fire reliably, consider giving them to a reloader to recycle the components.

Or sell them to someone you don’t like. Or simply discard them in your trash. If you burn your trash, disregard that last bit of advice, of course. At the same time, discarding them in the neighbor’s burning bin might not earn you a Neighbor of the Year award, either.

While most experienced shooters including myself will merrily dispose of (that’s spelled s-h-o-o-t) your “old” factory-loaded ammo, I avoid homemade reloads. You probably should too, unless you know the person who made them and trust them with your health and well-being.

Shooting someone else’s reloads carries an increased risk of problems.

People with attention deficit disorder sometimes don’t make good reloaders. Certainly neither do folks with early-onset Alzheimer’s or full-blown Dementia.

I’ve “inherited” reloads on a number of occasions in my life. Today, I pass them on to reloaders to recycle components. Those folks will usually discard the powder (it makes great garden fertilizer) and sometimes the primers, and then reload the cases with fresh, known powder and the original bullet.

Why don’t I like reloads? In short, squibs.

Squibs happen when the person or machine fabricating the cartridge failed to include a powder charge in the round. The primer of the squib will push the lead bullet into the barrel, where it will remain lodged. If the squib goes undetected, and a shooter then fires the next round into a now-obstructed barrel, bad things happen. In not so good cases, it can result in serious injury to the gun and shooter alike.

I have shot over 200,000 rounds in my life and the only squibs I’ve experienced came with shooting the home-rolled stuff.

Specifically, they all came from old folks who should have stopped reloading long before they finally did. In the last instance, the man failed to charge every third or fourth round with powder. I used a handful of them to make a malfunction video to show our students exactly what a squib load looks, feels and sounds like. And then I discarded the rest.

Unfortunately, squibs can wreck your barrel and potentially your firearm as well.

Barrel obstructions almost always destroy shotgun barrels, sometimes causing injuries too. A barrel obstruction in a high-powered rifle can cause a sudden and catastrophic disassembly of the receiver and chamber. And damage to all things nearby – including the shooter’s hands, arms and face.

Conversely, if a reloader double-charged the powder in a shell, that can also cause an unwanted, rapid discombobulation of things in your gun.

If you suspect you’ve inherited some reloads, my advice remains to pass them on to a reloader for components.

How do you identify reloads?

First off, rimfire ammunition is virtually always factory made.

With American-made centerfire rifle and pistol rounds, and shotgun shells, factory boxes usually serve as a clue. At the same time, one must inspect the individual shells in each box. Do they all share the same headstamps and color (nickel vs. brass)? Are the primers of uniform color? Are they all the same gauge or caliber (see above).

Do the headstamps match the box?

For instance, do the headstamps say Winchester in the Winchester box? Or do you have Remington rounds in a CCI or Fiocchi box?

If everything looks consistent and the case headstamps are uniform and match the brand on the box, the ammo is probably factory loaded. Furthermore, if the cartridges lack scratches, or other signs they have been loaded, fired or all of the above, that also suggests factory ammo.

In shotgun shells, do the shells all share the same color and print on the sides? Is the brass base of the shells uniform in height? Do the shells all appear to be factory crimped?

If so, that points to factory ammo.

Watch for any shells that look like they’ve been already fired and then reloaded (and re-crimped) like the shell on the left above.

Any rounds that show any signs of tampering like the 12-gauge shell above, right should find their way into your trash.

With all ammunition, all manner of shells can find their way into a box. Compare the shells for consistency – and gauge. If in doubt, take a pass on them. Or at the very least organize them. Don’t feed 16-gauge shells into your 12-gauge shotgun.

I mentioned American-made ammo above.

Old foreign ammo will also shoot in modern firearms of the appropriate caliber. However, some old foreign ammo may prove corrosive to some degree. For those who clean their gun before the sun sets, no problem. For those like me, you may find a light patina of rust on your barrel two weeks later. Lesson learned.

Remember, if you encounter old ammunition, do not use it for self-defense unless you have no other ammo available. Don’t buy someone’s old ammo to protect yourself and your family. Yes, even if you find some old .357 Magnum hollow-points.

Storing your ammo.

When buying ammunition, American or otherwise, you should store it in air-tight containers. Just coincidentally, military surplus ammo cans make great ammo storage containers for your ammo boxes. Regardless of container type, label the outside of the container, too. You will thank yourself later.

And for those who have more than a few rounds, ammunition cans make great organizers as well. Ideally, keep your ammo cans stored in a cool, dry place.

If you have an impressive ammo fort, don’t try to stack it tall and deep to minimize the footprint in wood-frame construction. Excessive weight, like numerous cases of 7.62×51 NATO, 5.56×45 (.223), 9mm Luger, .45 ACP and .38 Special can cause floor joists to sag over time. Ask me how I know.

In general, old factory-loaded ammo typically will retain its functionality for a long, long time.

Yes, even if it does not look pretty on the outside. One may encounter a few duds with really old or very poorly-stored ammo, but by and large it will go bang every time. To stay extra safe though, try to avoid reloaded ammo to reduce dangers from someone else’s home-made mistakes.